Robots

Robots have the potential not to replace humans, but go where humans can’t go, says CS major Julia Proft ’16.

By Edward Weinman

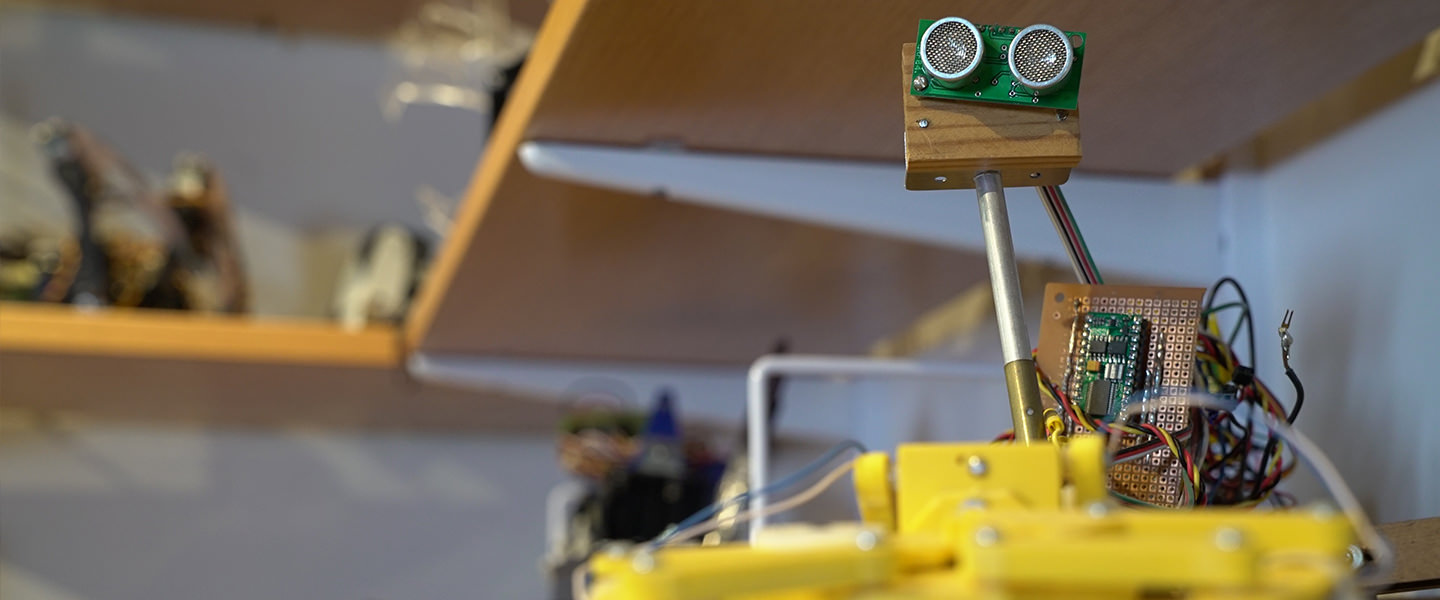

She named her robot Abracadabra. Why? Because Julia Proft ’16 is a fan of the Steve Miller Band, and her robot has a claw.

“My robot has an arm and can grab things,” Proft, a computer science major, says.

“The name was inspired by the Steve Miller song Abracadabra. 'You know, Abra-abra-cadabra, I want to reach out and grab ya,'” she sings. “It was a spur of the moment thing. I think the name is cute.”

This fall, Proft will be starting a Ph.D. program in computer science at Cornell, but at the moment she’s working with robots, more specifically, the utility of tethers, because she wants to use these machines to help first responders stay safe.

“There’s potential for robots, not to replace humans, but to go where humans can’t go and to collaborate with humans,” Proft says.

“Say you have a collapsed building or a nuclear disaster, you can’t send people in because it’s either impossible to get them in or because it’s a risk to their life. But you can send in robots.”

Proft explains that first responders also can’t send in autonomous robots to disaster areas because smoke or, let’s say, a radiation leak, wreaks havoc on the machine’s sensors. Therefore, a tether is necessary. However, tethers can limit a robot’s maneuverability (a tether twists or knots) so she prototyped Abracadabra to detach and reattach to its tether. While these types of robots already exist, the goal of Proft’s research is to discover ways to increase the utility of tethers.

“First responders have been looking for a robot that can detach itself from its power or communications cable, or even just a belay cable…because if a cable snaps in a disaster area most of the time you can’t just go in and retrieve the machine.

“And you’ve just lost a $25,000 robot.”

“You need a robot that can detach itself, roam around and do whatever it needs to do, and then reattach and get removed from the area.”

Proft’s robot research is part of her honors thesis, and she has been working under the supervision of Gary Parker, chair of the computer science department, who stands in a 8x8 foot enclosure, squared off by one-foot high walls made out of wood.

“It’s our colony space,” Parker says.

Looking to the ceiling, he points out a camera. “We can run experiments in this colony space, such as our predator-prey experiment.”